Though many business continuity standards emphasize the importance of tracking corrective actions to address identified issues, the recently published ISO 22301 (and previously BS 25999-2) also requires conducting a root cause analysis – looking not just at an issue, but its cause and how it can be prevented in the future. Root cause analysis (RCA) is an approach that seeks to proactively prevent reoccurrences of the same adverse event or systems failure by tracing causal relationships of a failure to its most likely impactful origin, then putting measures in place to mitigate underlying causes to ultimately help prevent recurrence of the adverse event in the future. While common in disciplines that deal with extreme precision and protection of life (e.g. quality and environmental health and safety), there’s no reason the business continuity discipline cannot benefit from a similar approach, particularly for practitioners looking to fully implement ISO 22301. This article explains root cause analysis and identifies how organizations can benefit from implementing the concept in a business continuity context.

The concept of root cause analysis was originally developed by Sakichi Toyoda (the founder of Toyota Motor Corporation), who developed a process called the “Five Whys” to understand potential causes for problems beyond what was immediately obvious. Root cause analysis became more formalized as it was integrated into several different fields as a performance driver, such as safety, quality, operations and information security. In each of these areas, reactively responding to an issue was not enough – future issues needed to be prevented, and root cause analysis was the path to enable improved performance and risk mitigation by eliminating true causes, rather than just symptoms. Incorporating root cause analysis into existing business continuity-related corrective action efforts could very well minimize the likelihood of future disruptive incidents and decrease recovery times.

At times, performing RCA is as easy as implementing the five whys, repeatedly asking “why” something occurred until it seems like you’ve reached the baseline cause of how failure occurred. The key is a disciplined application of asking probing questions. For example, analyzing the root cause of why an organization failed to meet a 24-hour recovery time objective for its SAP environment during a recent test could look something like this:

- Problem: IT recovery personnel failed to recover the organization’s SAP system within its recovery time objective of 24 hours during last week’s IT DR test …. Why?

- IT recovery personnel said that SAN LUNs were not mapped correctly, which drastically delayed the start of restoration from disk … Why?

- Vendor personnel responsible for prepping the equipment failed to execute the setup specifically to documented expectations … Why?

- Vendor personnel indicated that the instructions seemed contradictory and did not provide the level of detail necessary to execute steps, so they used a basic default setup …Why?

- Upon analysis, documentation did leave out several crucial steps necessary to enable this complex LUN mapping to occur …Why was this not found earlier?

- When performing previous testing, personnel did not fully leverage existing plan documentation … What changed this time?

- The individual responsible for documenting the plan and performing past testing was unavailable, and personnel who performed testing this time indicated they were not properly trained on use of the plans, nor were they instructed on how to escalate issues regarding recovery processes.

Although it might seem the root cause was reached, simply fixing the documentation does not ensure future documentation will be accurate. Taking it deeper, the previous IT subject matter expert responsible for documenting the procedures often does onsite testing without using documentation, as he has extensive experience in this field and felt he could perform tasks more quickly by recovering based on experience as opposed to documented procedures. Exploring the issue further revealed that newer personnel assigned to recovery tasks were far less experienced and had not yet received an appropriate level of awareness training. Related to this point, the IT Director admitted he never required other personnel to validate documentation, as testing takes time away from production support and leveraging the “experts” in each phase lessens testing time.

Part of the solution to this could be to implement an expectation that all documented procedures be validated at least annually by another IT individual within a different area of expertise. A second part of the solution could be to perform appropriate training up front (that emphasizes familiarity with plans and knowledge of escalation procedures) for both alternate internal individuals and any vendor resources responsible for plan execution. Together, these efforts could help assure that all IT DR documentation can be effectively used by both internal and external resources during testing.

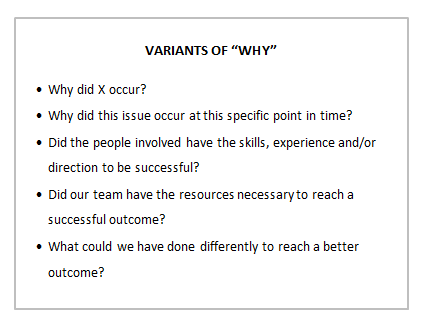

Although simple in theory, identifying the actual root cause and figuring out when you’ve gone far enough can be complex in practice. To help understand primary root causes, you must repeatedly ask variants of “why” (and a few other probing questions), then look for the answer that seems most likely to have influenced the issue. While there may not be a “hard science” to root cause analysis, the deeper you look for causes, the more likely you are to find issues to resolve. In most cases, the biggest issue most organizations face is not exploring problems in the first place! Our example demonstrated this problem in the recovery of SAP. However, it’s likely this problem (the shortcuts) exists in other areas, and addressing the root cause could improve performance and recoverability elsewhere.

Within business continuity, there are several areas that can commonly be identified as root causes for risk mitigation, response and recovery performance issues, although again, it requires tracing issues back further than most professionals choose to explore. To properly integrate root cause analysis into continuous improvement activities, each issue should be adequately documented, including source of issue, a detailed description, an identification date, and it should also have a field to capture root cause analysis. Rather than one individual trying to identify the root cause, business continuity personnel should organize and facilitate discussions that involve subject matter experts to whom issues may be assigned or who can provide insight on an issue, and then the group should seek to trace the issue back to its origin together.

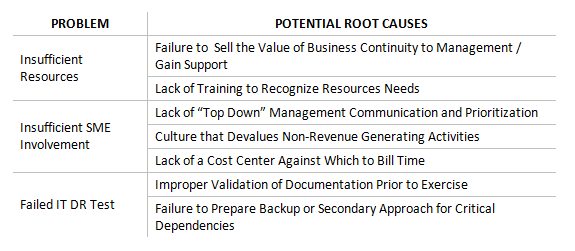

Within business continuity, there are numerous root causes that can lead to a variety of issues or complications. The following table notes a few examples, together with likely root causes, though this is far from a complete list. Also, it’s important to note that just like with tree roots that feed a tree’s growth, there could be more than one root cause that affects a system and results in a problem, so it is important to trace all potential paths of an issue’s origin back, rather than just pursuing one direct cause, to identify all influencing factors.

Again, root cause analysis is not just solving one instance of a problem, it’s also seeking opportunities to prevent future occurrences of an issue. Once the origin of an issue is identified, it’s important to evaluate all areas of the business to identify other at-risk areas and ensure proper risk mitigation measures are put in place. A solution in one area may not necessarily be applicable to all other areas of an organization, but even if it’s not, the act of identifying other similar at-risk areas raises awareness and enables the organization to develop additional solutions that make sense and address these risks before they result in future issues or downtime.

As business continuity management systems continue to mature, root cause analysis will become a powerful tool for business continuity professionals to deeply examine the cause of issues and provide an opportunity to correct them before they occur again.